As emergency services leaders, we always wonder why some people wait for so darned long before they call for help or why others simply refuse help until it’s far too late.

We work on our emergency notification messaging. We examine our use of social media. We conduct customer service surveys. We get together for mutual soul-searching brain-picking sessions trying to find ways to reach our populace in a timely manner, i.e., before they cross the threshold into life-or-death-and-probably-death territory.

What we consistently fail to recognize are the ties that bind. During the 1998 Ice Storm in Cote Saint-Luc, many people – especially the most vulnerable – were left with a stark choice: stay in dark, freezing homes and risk death or leave for the light and warmth of a community shelter. And despite constant round-the-clock door-knocking patrols by our medics we still couldn’t convince everyone who was medically fragile to evacuate. Heck, we couldn’t even convince them to answer the door.

Rather late in the timeline, after many middle-to-low income apartment buildings were evacuated, one of our crews thought they saw a light in a low-rise building that was supposed to be empty. Even the backup generator had failed and the sprawling building was freezing cold, silent and dark.

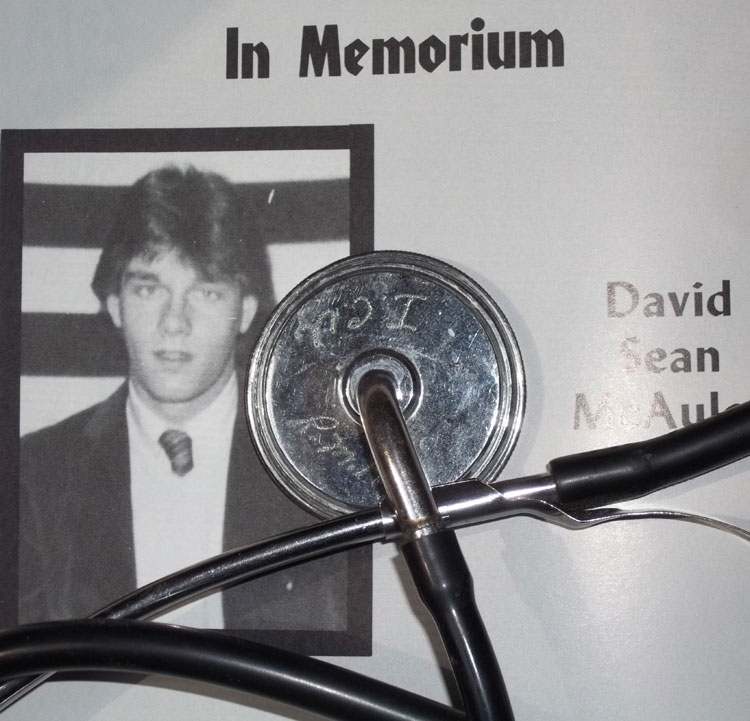

Our crew wandered the hallways quietly, listening carefully where they thought they had seen a the light through a window. Using a stethoscope against an apartment door, they heard shuffling footsteps inside. They knocked on the door. No answer. They pounded at the door. No answer.

It was so chilled and humid in that building our crew was getting cold and they were fully geared-up for the elements and then some. They requested permission for forcible entry stating concern for the occupant. With permission granted, they were about to force the door when it opened.

Standing inside was an eighty-something-year-old man wrapped in multiple layers of bathrobes standing in one of the tunnels that led from room to room in his apartment. There were pizza boxes stacked one atop the other, neatly, from floor-to-ceiling, covering every square foot of livingspace except for where he had created tunnels that led from the bathroom to the bedroom to the kitchen and to one corner of the diningroom where there was a chair and a small section of table visible.

It was surprisingly warm in the apartment. All of the windows were covered by pizza box towers save for one tiny peep hole overlooking the street. And that was where our crew had seen the flashlight as the man made his way from the kitchen to the bedroom.

“I always knew this day would come,” he said as he gathered up a small plastic bag of clothes.

“Which day? The Ice Storm?” our medics weren’t sure what he was talking about.

“No. The day when I would have to leave and never come back.”

“What are you talking about? We’ll just take you to the shelter and then after the Ice Storm you’ll be back here in your apartment.”

“No. That’s not going to happen. You’ll take me to the shelter and then you’ll file your report and then the social services people will come and visit the apartment and after they’re done the fire department will come and inspect and after that the geriatric psychiatry people will say I need to be moved into a seniors shelter and that’s where I will live until I die,” he said in matter-of-fact stream-of-consciousness manner.

Our medics tried to assure him he’d be back at home in a few days as they helped him lock his apartment and then made their way downstairs to the waiting rig.

He was, of course, correct.

He died a few weeks later in the antiseptic strangeness of an emotionally cold and grey hospital room where he was staying while awaiting placement in a seniors facility.

The ties that bind.

Be well. Practice big medicine.

Hal