A nugget of Big Medicine every day. #73 Learn to hold hands

Chris has big hands. When he shakes your hand there’s a sense of comfort that’s conveyed along with the warmth of his embrace.

Di and I were the first couple Chris married after he became a pastor.

We put him through some serious secular hoops for his first go at officiating at a wedding ceremony. Dropped all mentions of Jesus and Christ. Added Khalil Gibran, Robert Fulghum, and A.A. Milne. Nineteen years later and we’re still married and Chris was standing in the kitchen noshing on veggies and dip with the rest of the clan gathered for a visit. I guess that says good things on a number of levels: We’re still together and Chris and Betty still feel welcome in our home.

We compared notes on the common ground held by paramedics and pastors.

While each of us is trained to help people deal with extraordinary crises in their lives, much of our respective work comes down to an ability to ask open-ended questions while holding hands. Yes, it’s true, holding hands is our secret weapon against the forces of impossibly difficult emotional, mental, and physiological challenges.

And then there’s the learned ability to ask just the right open-ended questions designed to elicit a response that will provide framework and context for the current crisis.

When I was learning to be a paramedic, our textbooks were filled with lists of questions that were to be asked for all manner of ills. Do you have chest pain? Are you having difficulty breathing? How did you lose your fingers? The problem with those very narrowly-boxed questions is that the replies are often equally unrevealing. Yes. No. OhMyGod.

Damn. Where do we go from here.

I had a mentor who suggested that every single emergency should be treated as if we were walking into another social gathering. Take in your surroundings, look – really look at the people you’ll be talking with and listening to, breathe in the sights and sounds and the smells and then – after you’ve taken your own pulse and feel assured you can proceed without becoming a human sacrifice – introduce yourself and begin to choreograph that scene.

And that approach always worked wonders.

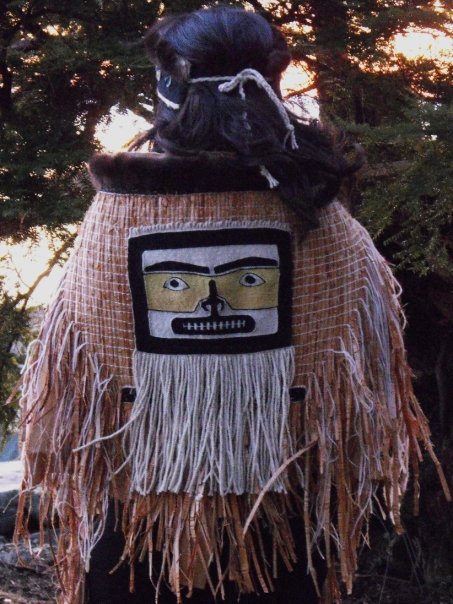

I remember being ushered into a cramped walk-up apartment in Montreal’s Cote-des-Neiges district by an anxious woman of Vietnamese descent. She spoke a rapid fire mix of French and Vietnamese so I understood about every third word. The apartment was filled with unfamiliar sounds and a mix of smells that assailed my sinuses.

There was the smell of cooking pork mixed with incense mixed with tiger balm mixed with the undeniable smell of sickness. In the livingroom/bedroom there was a futon mattress on the floor with a middle-aged man laying on it encircled by more than a dozen quietly anxious people all whispering in a mysterious mix of Vietnamese, French and English.

It was overwhelming.

We listened carefully to our guide and followed her into the room. Our patient, the man laying on the futon, had a series of strange deep red marks on his chest. It looked as if he had received a lashing with a whip. My partner and I exchanged alarmed glances. We were both thinking we needed to call for police assistance.

And then there was that smell – that super-mentholated-tiger-balm smell that even managed to overwhelm the smell of the soup being brewed in the kitchen and the tea being steeped on the balcony.

We paused. Our patient seemed to be having some difficulty breathing. He was conscious and alert and definitely did not seem to be in any emotional distress. There was no blood on the sheets and upon further examination, the marks on his chest seemed to look more like tattoos although they also seemed to be fading before our eyes.

I decided to use the social gathering approach. “Hello. My name is Hal and this is my partner Serge. Can you tell us why you called us today?”

And that’s how I learned about the practice of gua sha in traditional Vietnamese folk medicine. The marks we saw were caused by repeatedly rubbing the skin with the smooth edge of a coin pressed firmly against the man’s chest. Gua sha was performed in the hopes of ridding the patient of his chest cold. Except that in the process of the gua sha, the man – our patient – had developed some pretty intense chest pain. And that wasn’t part of the expected outcome so they called 911.

We weren’t able to determine if the chest pain was cardiac-related or was the result of the repeated application of pressure on his sternum so we transported him to ER at the Jewish General Hospital. The receiving physician and nurses were impressed with our knowledge of traditional Vietnamese folk medicine – which, of course, we had only amassed in the previous 45 minutes or so.

I found it interesting how a genuine interest in our surroundings, a held hand, and a willingness to listen while suspending judgment allowed us to bridge several thousand miles of cultural differences in a heartbeat.

We were invited back several times for soup and tea and always lovingly introduced as friends to neighbours and family.

Be well. Practice big medicine.

Hal