SUBSCRIBE TO BIG MED AT THE BIG MED SITE ON GOOGLE GROUPS.

November 10, 2009

| AMERICAS | OCEANIA | EUROPE | MIDDLE EAST | ASIA | POLITICS | BUSINESS | RESEARCH | EDUCATION | WORKFORCE |

Big Medicine is published by Team EMS Inc.

Managing Editor

Contact: ideas@tems.ca

Views

Contributor Emeritus

Tools

Stop Violence Against Women & Girls

The views expressed here reflect the views of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of their organizations. In particular, the views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Big Medicine, nor any member of Team EMS Inc.

TOOLS: WEATHER

Hurricane Season 2009

0821 NASA releases GOES-14 satellite video of Hurricane Bill -- NASA

has released a video of Hurricane Bill today from the GOES-14 satellite. The

video was put together from a series of still frames taken by the satellite

using both infrared and visible imagery and provides different views of

Hurricane Bill on August 20.

Earlier this summer, NASA launched the latest Geostationary Operational

Environmental Satellite, GOES-O. Recently operations have been turned over

to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the

satellite was renamed GOES-14. The satellite is still being tested in orbit,

and it captured video of Hurricane Bill on August 20, while it was on its

way to Bermuda.

The spectacular video is a collection of a few quick movies put together by

the GOES-14 team from the NASA GOES Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight

Center in Greenbelt, Md.

> View video

> View video

NASA and NOAA's newest weather satellite, GOES-14, has captured some

fascinating views of Hurricane Bill. This is a collection of a few quick

movies put together by the GOES-14 team. Credit: NASAOES Project

The video includes an impressive zoom-out, showing how big the hurricane is,

relative to the hemisphere. Bill is a large hurricane, more than 1,200

kilometers (746 miles) across, and the storm’s partially cloud-filled eye is

nearly 50 kilometers (31 miles) wide.

On August 20, the date of the movie, Hurricane Bill had sustained winds of

135 mph, making it a powerful Category 4 storm. At that time hurricane-force

winds extended outward up to 80 miles from the center. On August 21, Bill's

sustained winds were near 110 mph and hurricane force winds extended up to

115 miles.

0821 NASA watches as Hurricane Bill sweeps over Bermuda -- Hurricane

Bill is raining on Bermuda today, Friday, August 21, and NASA satellites are

providing forecasters with information about Bill's rainfall, clouds and

winds.

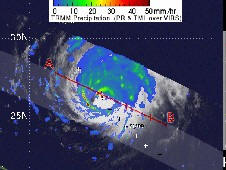

NASA and the Japanese Space Agency's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM)

satellite flew over the center of Hurricane Bill this morning capturing

rainfall data.

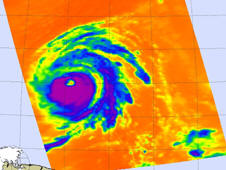

TRMM captured Hurricane Bill's heavy

rainfall on August 21 at 5:22 a.m. EDT. The yellow, green and red areas

indicate rainfall between .78 to 1.57 inches per hour. The red and purple

areas around Bill's eye are considered moderate to heavy rainfall.

Credit: NASA/SSAI, Hal Pierce

TRMM captured Hurricane Bill's heavy

rainfall on August 21 at 5:22 a.m. EDT. The yellow, green and red areas

indicate rainfall between .78 to 1.57 inches per hour. The red and purple

areas around Bill's eye are considered moderate to heavy rainfall.

Credit: NASA/SSAI, Hal Pierce

TRMM rainfall images are false-colored with yellow, green and red areas,

which indicate rainfall between 20 and 40 millimeters (.78 to 1.57 inches)

per hour. TRMM captured Hurricane Bill's heavy rainfall on August 21 at 5:22

a.m. EDT. The yellow, green and red areas indicate rainfall between .78 to

1.57 inches per hour. The red and purple areas around Bill's eye are

considered moderate to heavy rainfall.

According to the National Hurricane Center, Bill is expected to produce

total rain accumulations of 1 to 3 Inches over Bermuda, with maximum amounts

of 5 inches. Both a hurricane and tropical storm watch are in effect for

Bermuda as the rain continues.

For live radar of Bermuda, from the Bermuda Weather Service, visit:

http://www.weather.bm/radarLarge.asp.

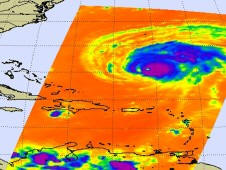

The Aqua satellite also flew over Hurricane Bill early today, Friday, August

21, and provided valuable data on his cloud top temperatures. They're

important because they tell forecasters how high thunderstorms are, and the

higher the thunderstorm, the more powerful it is, and Bill is pretty

powerful as a Category Three Hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Scale.

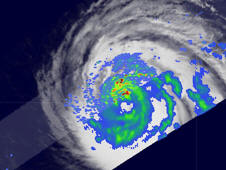

This infrared satellite image from the AIRS

instrument on NASA's Aqua Satellite shows Bill's clouds (depicted in purple

and blue) on August 21 at 2:11 a.m. EDT indicating high, cold powerful

thunderstorms. Credit: NASA JPL, Ed Olsen

This infrared satellite image from the AIRS

instrument on NASA's Aqua Satellite shows Bill's clouds (depicted in purple

and blue) on August 21 at 2:11 a.m. EDT indicating high, cold powerful

thunderstorms. Credit: NASA JPL, Ed Olsen

In infrared imagery, NASA's false-colored purple clouds are as cold as or

colder than 220 Kelvin or minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit (F). The blue colored

clouds are about 240 Kelvin, or minus 27F. The colder the clouds are, the

higher they are, and the more powerful the thunderstorms are that make up

the cyclone.

Although Bill has weakened slightly over the last 24 hours, forecasters say

it could regain a little strength before winds and cooler waters start

battering it and weakening it. Bill is forecast to parallel the eastern U.S.

coast and affect Nova Scotia, Canada, on its curved track into the North

Atlantic Ocean this weekend. As Bill approaches the Canadian Maritimes it

will undergo a transition into an extratropical storm.

At 11 a.m. EDT, Hurricane Bill had maximum sustained winds near 115 mph. He

was moving northwest near 18 mph and is expected to turn to the

north-northwest later today. His center is currently near latitude 27.6

north and longitude 66.3 west or about 335 miles south-southwest of Bermuda

and about 755 miles southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Minimum

central pressure is 958 millibars.

Meanwhile a warning is in effect now about large, and dangerous ocean swells

for a huge area in the eastern Atlantic. Large swells associated with Bill

will be impacting the coasts of Puerto Rico; Hispaniola; the Bahamas;

Bermuda the entire eastern United States; and the Canadian Maritimes. The

National Hurricane Center warns "These swells will likely cause extremely

dangerous surf and life-threatening rip currents. Please consult output from

your local weather office for details."

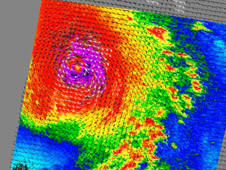

0820 NASA's QuikScat sees Cat 3 Hurricane Bill's winds go a long distance

-- NASA satellites continue to capture important wind speed and cloud data

that forecasters at the National Hurricane Center are using to help their

forecasts. QuikScat has been particularly helpful in determining the extent

of hurricane and tropical storm-force winds, and they go a great distance.

NASA's QuikScat satellite uses microwave technology to peer through the

clouds and measure the surface winds of a tropical cyclone. On Thursday,

August 19, QuikScat data found that Bill's hurricane force winds have

dropped down to a Category 3 hurricane at 125 mph. However, forecasters note

that Bill is moving into an area that could help him strengthen back to

Category 4 hurricane on Friday or Saturday.

QuikScat used microwaves to peer through

Bill's clouds and measure his winds on August 18 at 5:23 p.m. EDT when Bill

was a powerful Category 4 hurricane. Credit: NASA JPL, Peter Falcon

QuikScat used microwaves to peer through

Bill's clouds and measure his winds on August 18 at 5:23 p.m. EDT when Bill

was a powerful Category 4 hurricane. Credit: NASA JPL, Peter Falcon

Bill's hurricane-force winds extend up to 85 miles from his center, about

the distance from Staten Island, N.Y. to Philadelphia, Penn. Bill's Tropical

storm force winds extend to as far as 230 miles from the center, and that's

about the distance from New York City, N.Y. to Washington, D.C.!

At 5 a.m. EDT on August 19, Bill's maximum sustained winds had decreased to

125 mph, and he was moving northwest near 18 mph. That motion is expected to

continue for a day until he turns to the north-northwest late Friday.

Minimum central pressure was 949 millibars. Bill was located about 790 miles

south-southeast of Bermuda and only 325 miles north-northeast of the Leeward

Islands.

NASA's Terra satellite also flew over Bill, and using the Moderate Imaging

Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument captured an image of the storm when it

was located off the Lesser Antilles in the Atlantic Ocean on August 19 at

12:15 p.m. EDT. MODIS showed a strong hurricane with a well-defined eye.

NASA's MODIS instrument on the Terra

satellite captured Hurricane Bill, located off the Lesser Antilles in the

Atlantic Ocean on August 19 at 12:15 p.m. EDT. Credit: NASA, MODIS

Rapid Response

NASA's MODIS instrument on the Terra

satellite captured Hurricane Bill, located off the Lesser Antilles in the

Atlantic Ocean on August 19 at 12:15 p.m. EDT. Credit: NASA, MODIS

Rapid Response

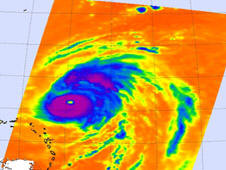

NASA's Aqua satellite joined QuikScat and Terra to capture Hurricane Bill. Aqua's Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument captured Bill's frigid cloud temperatures on August 20 at 1:29 a.m. EDT. The imagery clearly showed Bill's 30- mile wide eye in the center of the storm, and indicated Bill's high thunderstorm cloud temperatures were colder than minus 63 Fahrenheit.

NASA's AIRS instrument on the Aqua

satellite caught Bill's icy cold clouds on August 20 at 1:29 a.m. EDT as it

was moving toward the Leeward Islands (left of the storm). Notice Bill's 30

mile wide eye is well-defined in the center of the storm. In this

false-colored image, purple indicates Bill's high thunderstorm cloud

temperatures are colder than minus 63F and blue is minus 27F or colder.

Credit: NASA JPL, Ed Olsen

NASA's AIRS instrument on the Aqua

satellite caught Bill's icy cold clouds on August 20 at 1:29 a.m. EDT as it

was moving toward the Leeward Islands (left of the storm). Notice Bill's 30

mile wide eye is well-defined in the center of the storm. In this

false-colored image, purple indicates Bill's high thunderstorm cloud

temperatures are colder than minus 63F and blue is minus 27F or colder.

Credit: NASA JPL, Ed Olsen

Hurricane Bill is hundreds of miles away from the U.S. coast today, but

forecasters are cautioning about large swells the storm is creating already.

The National Hurricane Center noted that "Large swells associated with bill

will be impacting the islands of the northeast Caribbean Sea, the Bahamas

and Bermuda during the next day or two." Meanwhile, residents along the east

coast of the U.S. should be on watch, starting Friday and over the weekend,

as large swells will begin to affect areas of the coast. Rip tides may also

be possible, so beachgoers and boaters should be aware of the hazardous

conditions Bill will create along the coasts this weekend.

The National Hurricane Center in Miami, Fla. is forecasting Bill to pass to

the west of Bermuda and then track parallel to the U.S. east coast over the

weekend, stirring up the ocean.

0819 NASA's Aqua Satellite gets two views of Category Four Hurricane Bill

-- Hurricane Bill has become a powerhouse in the Atlantic Ocean and NASA

satellites are providing forecasters with important information to help

their forecasts. Bill is now a category four hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson

Scale and is expected to strengthen as it nears Bermuda, and NASA's Aqua

satellite captured two views of his cloud cover.

On Wednesday, August 19, at 5 a.m. EDT, Bill's maximum sustained winds are

near 135 mph, and hurricane force-winds extend out to 45 miles from Bill's

large 35-45 mile-wide eye. Bill was closing in on the Leeward Islands, about

460 miles east of them, near 18.0 degrees north latitude and 54.9 west

longitude. Bill continued to move west-northwest at 16 mph and had a minimum

central pressure near 948 millibars.

AIRS

captured Hurricane Bill's cold clouds with infrared imagery on August 18 at

12:35 p.m. EDT. The infrared revealed very cold high clouds, indicating a

powerful hurricane. Credit: NASA JPL, Ed Olsen

AIRS

captured Hurricane Bill's cold clouds with infrared imagery on August 18 at

12:35 p.m. EDT. The infrared revealed very cold high clouds, indicating a

powerful hurricane. Credit: NASA JPL, Ed Olsen

NASA's Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument on the Aqua satellite

captured Hurricane Bill's cold clouds with infrared imagery on August 18 at

12:35 p.m. EDT. The infrared revealed very cold high clouds, indicating

strong thunderstorms and a powerful hurricane. Infrared imagery is useful to

forecasters because it shows the temperature of the cloud tops, helping

recognize if powerful thunderstorms exist in the storm. AIRS infrared

imagery showed Bill's thunderstorm clouds are cold as or colder than 220

Kelvin or minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit (F)!

Meanwhile, the Moderate Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS instrument on Aqua satellite captured a stunning image of Hurricane Bill on August 18 at 2:40 p.m. EDT, clearly showing his large eye.

The

MODIS instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite captured this stunning image of

Hurricane Bill on August 18 at 2:40 p.m. EDT. Credit: NASA MODIS Rapid

Response Team

The

MODIS instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite captured this stunning image of

Hurricane Bill on August 18 at 2:40 p.m. EDT. Credit: NASA MODIS Rapid

Response Team

Bill's track has been the question on the minds of U.S. East Coast

residents, and currently the models are indicating two different scenarios.

According to the National Hurricane Center discussion this morning, August

19, "The track guidance models forecast Bill to gradually turn northwestward

towards this weakness during the next 48-72 hours."

There's a large "deep-layer trough" – an elongated area of low pressure,

associated with a cold front that is moving into the eastern United States,

and forecasters think that front is going to push Bill eastward and curve

him north and northeastward. Bill's track depends on the strength of the

front and the timing, so one model calls for Bill to go near New England

while other computer models have him taking a sharp turn out to sea.

Forecasters and East Coast residents are hoping the front pushes Bill out to

sea.

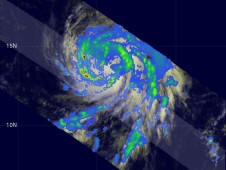

20090819 NASA's TRMM satellite sees wide-eyed Hurricane Bill strengthening--The TRMM satellite noticed a wide-eyed Hurricane Bill's rainfall is intensifying indicating he's getting stronger. Satellite images have also shown Bill's eye is widening.

TRMM captured Hurricane Bill's heavy

rainfall on August 17 at 10:25 p.m. EDT. The yellow, green and red areas

indicate rainfall between .78 to 1.57 inches per hour. Red areas are

considered moderate rainfall. Credit: NASA, Hal Pierce

NASA and the Japanese Space Agency's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM)

satellite flew over the center of Hurricane Bill on August 18, 2009 at 0225

UTC (August 17 at 10:25 p.m. EDT) capturing rainfall data.

TRMM rainfall images are false-colored with yellow, green and red areas,

which indicate rainfall between 20 and 40 millimeters (.78 to 1.57 inches)

per hour. Red areas are considered moderate rainfall.

The TRMM rainfall analysis from the TRMM Microwave Imager (TMI) and

Precipitation Radar (PR) instruments reveal that hurricane Bill has an eye.

This feature isn't apparent on the TRMM Infrared image (VIRS) but is

evidence of Bill becoming a stronger category two hurricane with wind speeds

increasing to about 85 knots (~98 miles per hour). In fact, satellite

imagery shows that Bill's eye is quite large, between 35-45 nautical miles

in diameter!

At 11 a.m. EDT, Hurricane Bill had maximum sustained winds near 105 mph,

making him a Category Two on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. He is expected to

strengthen into a Category Three hurricane, a major hurricane, with winds in

excess of 110 mph. Bill was centered about 705 miles east of the Leeward

Islands, near 15.9 north and 51.2 west. He was heading west-northwest near

16 mph with a minimum central pressure of 963 millibars.

Interests in the Leeward Islands should monitor Bill's progress, as his

track is currently expected to remain at sea and sweep past them and head in

a northwesterly direction over the next two days.

20090818 Two NASA satellites capture Hurricane Bill's 'baby pictures'--Bill was the third tropical depression in the Atlantic Ocean hurricane season, behind Ana and Tropical Depression One. Over the weekend Bill grew into the first hurricane in the Atlantic this season. Two NASA Satellites captured Bill's rainfall and cloud temperatures as he was powering up.

The TRMM satellite flew over the large and

well-organized Hurricane Bill at 7:33 a.m. EDT on August 17 indicating bands

of heavy rainfall. Credit: NASA, Hal Pierce

Hurricane Bill was upgraded to a hurricane by the National Hurricane Center

(NHC) in Miami, Florida on August 17 at 5 a.m. EDT. The Tropical Rainfall

Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite flew over hurricane Bill a short time

later at 1133 UTC (7:33 a.m. EDT) and captured Bill's "baby picture" shortly

after he became a hurricane.

Data from the TRMM over flight was used in making the rainfall analysis at

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt Md. The rainfall analysis

showed that Bill was already a large and well- organized hurricane. TRMM's

Microwave Imager and Precipitation Radar instruments revealed that Bill has

bands of heavy rainfall.

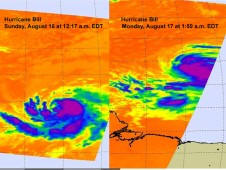

This is a time series of two AIRS images of

Hurricane Bill on August 16 at 12:17 a.m. EDT (left) and August 17 at 1:50

a.m. EDT (right) showing the cold temperatures in his thunderstorms,

indicative of heavy rainfall. Credit: NASA/JPL, Ed Olsen

NASA's Aqua satellite captured Hurricane Bill on August 16 at 12:17 a.m. EDT

and August 17 at 1:50 a.m. with the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS)

instrument. AIRS measures cloud temperature using infrared light. In NASA's

infrared imagery, the false-colored purple clouds are as cold as or colder

than 220 Kelvin or minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit (F). The blue colored clouds

are about 240 Kelvin, or minus 27F. The colder the clouds are, the higher

they are, and the more powerful the thunderstorms are that make up the

cyclone and Bill has some high thunderstorms.

On Monday, August 17 at 11 a.m. EDT, Bill continued strengthening and is

expected to become a major hurricane - that is a Category Three hurricane,

by Wednesday. Today, however, Bill had sustained winds near 90 mph, and the

hurricane force winds extended 30 miles out from the center. Bill was moving

west-northwest near 16 mph and had a minimum central pressure near 977

millibars. Bill was centered about 1,080 miles east of the Lesser Antilles,

near 14.1 north and 45.2 west.

Bill is predicted by the NHC to become a dangerous category three storm in

the next three days with winds of 110 knots (~126.5 miles per hour).

20090818 Tropical Storm Claudette makes landfall in Florida--By

mid-day today, Monday, August 17, Claudette's center had moved into

southwestern Alabama and weakened into a tropical depression. She'll turn

toward the north-northwest later today and soak Alabama with up to 10 inches

of rain in some isolated areas.

At 2 a.m. EDT on Monday, August 17, Tropical Storm Claudette made landfall

near Fort Walton Beach, Florida with maximum sustained winds near 50 mph.

When it made landfall, tropical storm force winds extended 70 miles from the

center, so towns from 70 miles to the east and west of Claudette's center

received sustained winds over 37 mph.

The National Hurricane Center in Miami, Florida issued their last advisory

on Claudette this morning at 7 a.m. EDT. Now, NOAA's Hydrometeorological

Prediction Center (HPC) is issuing forecasts on Claudette as she moves

through the interior U.S. At 10 a.m. EDT today, the HPC said that Claudette

will track north-northwest through southwestern Alabama and northern

Mississippi tonight.

The HPC expects "More precipitation to break out during the day across

Alabama and the Florida panhandle mainly east of the circulation center."

They "suspect that tonight there will be the potential for very heavy

rainfall amounts near the center as it reaches into northern Mississippi,

especially in overnight hours when convection often flares near the center

of circulation. Still expect the potential for 3 to 6 inch totals with

Claudette...and isolated totals up to 10 inches mainly within the stationary

bands of rainfall across the Florida panhandle."

At 8 a.m. EDT the center of tropical depression Claudette was located near

latitude 31.3 north and longitude 87.2 about, 15 Miles North-Northwest of

Brewton, Alabama and about 85 miles southwest of Montgomery, Alabama. She

was moving northwest near 12 mph. Claudette's sustained winds were down to

35 mph, and she'll continue to weaken today as she moves farther inland. The

estimated minimum central pressure is 1011 millibars.

The National Weather Service in Tallahassee reported that the cities of

Apalachicola and St. George areas saw a combined 4-6 inches of rain since

Sunday morning. The highest wind gust in Apalachicola was reported at 50

mph.

NASA's Aqua satellite captured Tropical Storm Claudette on Sunday, August 16

at 2:30 p.m. EDT (1:30 p.m. CDT) about 12 hours before her eye made landfall

near Fort Walton Beach, Florida. The image was captured by the Moderate

Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument. The Atmospheric Infrared

Sounder (AIRS) instrument that measures cloud temperature using infrared

light. The higher the clouds are, the colder they are. One interesting thing

that AIRS showed forecasters was that the extent of the cloud cover almost

doubled in 11 hours on Sunday, August 16 between 3:29 a.m. EDT and 2:29 p.m.

EDT, when AIRS captured images of Claudette.

Now, residents of Alabama and Mississippi should expect heavy downpours and

localized flooding from Claudette's rains. The system is expected to move

toward the northwest and by tomorrow it is expected to have weakened to a

depression over western Tennessee.

20090818 Tropical Depression Ana drenching Puerto Rico--Tropical

Depression Ana is currently drenching Puerto Rico, and tropical storm

watches are posted for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands as Ana continues

westward. Both the Aqua and GOES satellites have captured Ana on her

westward track in the Atlantic.

For a live look at the National Weather Service Radar in Puerto Rico

Tropical Depression Ana has taken a long time to get going and she's still squeaking by as a tropical depression. Over the weekend, NASA satellite imagery captured her short stint as a tropical storm, but she's weakened again and is expected to now rain on Hispaniola before heading to Florida.

By 11 a.m. EDT on Monday, August 17, Ana's center was located 75 miles south of San Juan, Puerto Rico, near 17.3 north and 66.2 west. She was moving at a good clip toward the west-northwest near 28 mph, which means that she won't linger as long and dump as much rain. However, she's expected to slow down in the next day or two. Maximum sustained winds remain near 35 mph, and minimum central pressure is 1008 millibars.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) flies on Aqua and provides visible, infrared and microwave images and measures cloud top temperature and pressure. AIRS captured an image of Ana on August 15 when she was a tropical storm and had good cloud formation. By mid-day on August 16, Ana deteriorated into a tropical depression.

How does infrared imagery know how high clouds are in the sky? The coldest ones are higher in the sky (because in the troposphere, the lowest layer of atmosphere where weather happens, temperatures fall the higher up you go until you get to the stratosphere). The highest clouds are as cold as or colder than 220 Kelvin or minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit (F) and second highest level of clouds are about 240 Kelvin, or minus 27F. The colder the clouds are, the higher they are, and the more powerful the thunderstorms are that make up the cyclone.

Another satellite that NASA uses is the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite, or GOES. GOES-12 covers the Atlantic Ocean, and is managed by NOAA. On August 17 at 12:15 p.m. EDT, GOES-12 captured Tropical Depression Claudette over Alabama, and Tropical Depression Ana raining on Puerto Rico.

Forecasters are closely watching Ana because she may degenerate further. However, her remnants or the depression, whichever she becomes, is expected to track to Florida's west coast.

Caribbean: PAHO releases new wind hazard maps

[May 28 Washington DC]--The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief Coordination unit, through Applied Research Associates, has developed new state-of-the-art wind hazard maps for Caribbean islands and nearby coastal areas of Central and South America. The maps use the most up-to-date meteorological records and methods and are intended to replace older maps currently in use for structural design and risk assessment. They are an important aid for engineers, developers, and others whose work requires knowledge of wind hazards.The new maps, created by PAHO’s Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief Coordination unit through Applied Research Associates, benefit from more than 20 years' worth of new data collected since the last Caribbean regional wind hazard map for engineering design purposes was developed in 1985. Moreover, they are based on the latest developments in hurricane forecasting and tracking and estimation of wind speed and direction, which are recognized by consensus in the scientific community.

Reliable wind hazard information is crucial for the work of engineers whose projects must resist hurricane-force winds, for building developers or owners who wish to specify the level of safety of their facilities, and for insurance providers who wish to know the risks they underwrite. Financial institutions also sometimes wish to specify wind design criteria for their projects.

Currently, regional building standards for wind resistance are laid out in the 1985 Caribbean Uniform Building Code (CUBiC). The higher-than-normal hurricane activity in the North Atlantic over the past 13 years has led to the questioning of wind design criteria incorporated in the present standards in the Caribbean. A project funded by the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) and executed by the Caribbean Regional Organization for Standards and Quality (CROSQ) is currently developing new regional standards to replace the CUBiC. However, this project does not include new wind hazard maps for the region. The new PAHO Caribbean Basin Wind Hazard Maps are consistent with the CDB-CROSQ process in that both are based on U.S.A. "International" codes that reference the wind load provisions of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The new Caribbean Wind Hazard Maps were developed in consultation with regional meteorologists, officials and experts from PAHO member countries, regional engineers and architects. This open consultation process, coordinated by Caribbean engineer Tony Gibbs, was followed to facilitate the adoption of the maps by Caribbean communities. Funding for the project was provided by the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance of the U.S. Agency for International Development (OFDA/USAID).

Why were new wind hazard maps prepared?

1. The present project includes the Caribbean coastlines of South and

Central American countries. In several of these cases there is no presently

available wind hazard guidance for structural design purposes. The new maps

will plug that gap.

2. The only pan-Caribbean wind hazard maps ever produced for application in the design of structures were in 1969 (Caribbean Meteorological Institute – H C Shellard), 1981 (Caribbean Meteorological Institute – B Rocheford), 1985 (University of Western Ontario Boundary Layer Wind Tunnel Laboratory – Davenport, Surry, Georgiou).

3. Since 1985 the region has collected another 23 years of relatively reliable data. The incorporation of these data would serve to improve the quality of currently-available wind hazard information.

4. There have been developments in the science and technology related to the long-term forecasting of hurricane activity in the North Atlantic (including the Caribbean).

5. The past 13 years of higher-than-normal hurricane activity in the North Atlantic has led to the questioning of wind design criteria incorporated in the present standards in the Caribbean.

6. This, in turn, has led to uninformed and unreasonable and counterproductive decisions on appropriate basic (and therefore design) wind speeds for some Caribbean projects and in some Caribbean countries.

7. The phenomenon of hurricane activity in the Caribbean is best dealt

with regionally and not in a country-by-country manner.

What use will be made of the results of the proposed project?

1. New regional standards are currently being prepared in a project funded

by the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) and executed by the Caribbean

Regional Organisation for Standards and Quality (CROSQ). These will replace

the Caribbean Uniform Building Code (CUBiC). The CDB-CROSQ project does not

include new wind hazard maps for the target region. These new Caribbean

Basin maps have been prepared to be consistent with the CDB-CROSQ intension

to base the new standards project on the USA “International” codes which

reference the wind load provisions of the American Society of Civil

Engineers (ASCE 7 Chapters 2 and 6). Thus the results of this wind hazard

mapping project could be plugged directly into the new CDB-CROSQ standards.

2. Those Caribbean countries which, for whatever reason, are developing their own standards and not participating in the CDB-CROSQ project will also require wind hazard information. This wind hazard mapping project will provide wind hazard information which could readily be represented in forms designed to fit directly into standards documents with different approaches. (Technical standards in the Caribbean are best dealt with regionally and not in a country-by-country manner. This comment relates particularly to the Commonwealth Caribbean.)

3. Engineers in all Caribbean countries are designing projects every day

which must resist the wind. Confidence in the wind hazard information is

important to designers. Clients sometimes wish to specify the levels of

safety of their facilities. Insurance providers sometimes wish to know the

risks they underwrite. This depends critically on the quality of hazard

information. Financing institutions sometimes wish to specify wind design

criteria for their projects. There is, in summary, an immediate and palpable

need for wind hazard information based on up-to-date meteorological records

and methodologies recognised by consensus in the scientific community.

The open process adopted in his project is exemplified by:

1. The present Caribbean Basin Wind Hazard Maps (CBWHM) project has prepared a series of overall, regional, wind-hazard maps using uniform, state-of-the-art approaches covering all of the Caribbean islands and the Caribbean coastal areas of South and Central America. The project was executed in consultation with interest groups throughout the target region.

2. An interim, information meeting was held at PAHO in Barbados on 01 October 2007. Meteorologists, engineers, architects, emergency managers, standards personnel and funding agency personnel from the wider Caribbean were invited (and were funded) to attend.

3. At that meeting the principal researcher, Dr Peter Vickery of Applied

Research Associates (ARA) described the methodology for developing the maps;

presented the interim results available at the time of the meeting; received

comments from participants and answered their questions; discussed what

systems need to be put in place to improve knowledge of the wind hazard in

the Caribbean region and outlined the further work to finalise the present

mapping exercise.

Online:

Urban weather: Cities incite thunderstorms

[Aug 10 Princeton NJ USA]--Summer thunderstorms become much more fierce when they collide with a city than they would otherwise be in the open countryside, according to research led by Princeton engineers.Alexandros A. Ntelekos and James A. Smith of Princeton University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science based their conclusion on computer models and detailed observations of an extreme thunderstorm that hit Baltimore in July of 2004.

Their modeling suggests that the city of Baltimore experienced about 30 percent more rainfall than the region it occupies would have experienced had there been no buildings where the city now sits.

This

picture shows the pattern of lightning strikes near

Baltimore and Washington, D.C. during the rare and extreme

2004 thunderstorm.

This

picture shows the pattern of lightning strikes near

Baltimore and Washington, D.C. during the rare and extreme

2004 thunderstorm.

While thunderstorms are thought of as being purely forces of

nature, the Princeton research suggests that man’s built

environment can radically alter a storm’s life cycle.

A storm of the intensity of the 2004 event in Baltimore is

extremely rare, occurring only once every 200 years or so.

However, climate change is expected to make such events more

frequent, according to the fourth assessment report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Precipitation events like gully-washing rainstorms are

expected to increase in intensity as the world warms due to

the buildup of greenhouse gases,” said Michael Oppenheimer,

a lead author on the IPCC report and the Albert G. Milbank

Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at

Princeton. “This is just the sort of research that combines

science, engineering, and social response that may allow us

to better cope with the future, warmer climate. I hope it

will also serve as a warning about the complexity of

adaptation, and therefore, as a goad to policymakers to act

more urgently to stabilize the climate.”

In yesterday’s intense storm in New York City -- which

played havoc with subways, street traffic, and airports –

about three inches of rain fell in one hour. In the 2004

storm that the researchers studied, about six inches fell

within two hours.

“The storm that occurred yesterday in New York City is an

example of the sort of event that we expect more of in the

future,” said Oppenheimer. “The disruptive effect was quite

obvious.”

Observational data shows that, during the 2004 storm, parts

of Baltimore experienced as many lightning strikes in the

space of two hours as they normally receive during the

course of a year.

Much of the lightning during the 2004 storm wrapped around

the western edges of Baltimore and Washington, D.C., to the

south. “It’s as if all of a sudden the lightning can ‘feel’

the city,” said Ntelekos, a Princeton graduate student in

civil and environmental engineering who is a fellow with the

Woodrow Wilson School’s Science, Technology, and

Environmental Policy (STEP) program.

The interaction between storm and city has serious

consequences for urbanites as well as policymakers.

“This means that warm-season thunderstorm systems will

probably increasingly lead to more flash flooding, which can

be very dangerous,” said Smith, a professor of civil and

environmental engineering at Princeton.

Hydrologists have observed evidence in the past that urban

environments alter the behavior of storms. But they have

mostly noted average increases in rainfall over long periods

of time. Until now, they have not made observations of

specific extreme storms because they lacked the right tools

to do so.

The National Science Foundation-funded research by Ntelekos

and Smith pieced together many different pieces of

observational information on lightning strikes, rainfall,

clouds and aerosols -- which they combined with analyses

based on computer models of the atmosphere.

This figure shows the trajectories (represented by the white lines) of what were initially two storm-cells

The combined data yielded surprising conclusions. For

example, neighboring cities also can affect the behavior of

a storm. The Ntelekos-Smith research showed that the 2004

storm over Baltimore was partially affected by the

neighboring urban environment of Washington D.C. as air from

the south became more turbulent when passing over it. This

made the air mass particularly ripe for a storm by the time

it reached Baltimore.

The scientific consensus so far has been that, during a

storm, greater rainfall occurs on the downwind part of the

city than on the upwind side.

However, the researchers found that during the 2004

Baltimore storm, the western part of the city -- not the

upwind, northern part -- was hit harder by rainfall and thus

extreme flooding, according to Ntelekos.

“Previous studies basically came from cities where the

terrain was simple, where you had a town in the middle of

nothing -- no mountains, no water,” he said. “But most of

the hub cities are close to either mountains or water as

well as being close to other cities. So we have to

understand how extreme thunderstorms behave over complex

terrains.”

Ntelekos and Smith are presenting some of their research

this week at a workshop sponsored by MIRTHE, a National

Science Foundation Engineering Research Center at Princeton

University.

Exactly how does the urban environment alter the evolution

of thunderstorms" The researchers described three

mechanisms:

Urban heat islands: Cities produce heat and are often 2 to 5

degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the surrounding environment.

In milder storms, this “heat island” can provide fuel for a

modest thunderstorm. But in their study of the 2004

thunderstorm, the Ntelekos and Smith found that the heat

island had little effect because high winds leveled

temperatures.

Urban canopies: While forests have tree canopies, cities

have building canopies. The height and placement of

buildings alters a storm’s low-level wind field, a key

ingredient in its behavior. The tall buildings increase wind

drag on the city, resulting in vertical velocities –

essentially a boiling action – that can enhance rainfall.

The urban canopy had a large effect during the 2004 storm,

the researchers found, which was exacerbated all the more by

the presence of the Chesapeake Bay to the east.

Urban aerosols. These are essentially minuscule particles in

the atmosphere that are at elevated levels in urban

environments due to industrial and automobile emissions.

Traditionally, researchers have thought that air pollution

tends to suppress precipitation. But Ntelekos and Smith

believe their research points to the possibility that urban

aerosols actually increase rainfall.

Ntelekos plans to build on his Baltimore research in a more

detailed study of the effect of aerosols on thunderstorms in

New York City. That research will be a testbed for

laser-based sensor technologies being developed by

Princeton’s MIRTHE center, which is charged with developing

next-generation sensor technology for the environmental

monitoring, medical diagnostics and national security.

Ntelekos and Smith have written a paper that describes the

findings of the 2004 storm over Baltimore and which is

currently under review by the Water Resources Research

journal published by the American Geophysical Union. Their

coauthors on this paper are Krajewski and Radoslaw Goska of

the University of Iowa; Mary Lynn Baeck of Princeton; and

Andrew J. Miller of the University of Maryland, Baltimore

County. Ntelekos and Smith are also coauthors with Witold F.

Krajewski, Chair of Water Resources Engineering at the

University of Iowa, of a recent paper in the Journal of

Hydrometeorology which describes links between summer

thunderstorms and flash flooding in the Baltimore

metropolitan region.

PAPER ABSTRACT: The climatology of thunderstorms and flash

floods in the Baltimore, Maryland, metropolitan region is

examined through analyses of cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning

observations from the National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN)

and discharge observations from 11 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

stream gauging stations. A point process framework is used

for analyses of CG lightning strikes and the occurrences of

flash floods. Analyses of lightning strikes as a space–time

point process focus on the mean intensity function, from

which the seasonal, diurnal, and spatial variation in mean

lightning frequency are examined. Important elements of the

spatial variation of mean lightning frequency are 1)

initiation of thunderstorms along the Blue Ridge, 2) large

variability of lightning frequency around the urban cores of

Baltimore and Washington D.C., and 3) decreased lightning

frequency over the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Ocean.

Lightning frequency has a sharp seasonal maximum around

mid-July, and the diurnal cycle of lightning frequency peaks

between 2100 and 2200 UTC with a frequency that is more than

an order of magnitude larger than the minimum frequency at

1200 UTC. The seasonal and diurnal variation of flash flood

occurrence in urban streams of Baltimore mimics the seasonal

and diurnal variation of lightning. The peak of the diurnal

frequency of flash floods in Moores Run, a 9.1-km2 urban

watershed in Baltimore City, occurs at 2200 UTC. Analyses of

the lightning and flood peak data also show a close link

between the occurrence of major thunderstorms systems and

flash flooding on a regional scale.

FULL CITATION: Ntelekos, A.A., J.A. Smith and W.F. Krajewski,

Climatological Analyses of Thunderstorms and Flash Floods in

the Baltimore Metropolitan Region, Journal of

Hydrometeorology, 8(1), 88-101, 2007.

NOAA news conference on the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season

outlook

[May 23 07 Arlington VA USA]--Mr. Franklin: Good morning.

Welcome to the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season outlook. My

name is Anson Franklin, Director of Communications with NOAA.

We have several speakers here today to talk about the

hurricane outlook.

We have information about the sequence of appearance in your

press kits. And as soon as they finish speaking, we will

have about – we will have a few minutes to take questions

from you. And at that point, I’ll just point out the

questioner, then we’ll take it from there.

Starting off is the Administrator of NOAA, Admiral Conrad

Lautenbacher.

Admiral Lautenbacher: Thank you, Anson. Good morning, ladies

and gentlemen, and thank you all for coming today. This is,

I think, as everybody realizes, the first event of National

Hurricane Awareness Week. This is our Atlantic seasonal

outlook, and one of our most highly anticipated

announcements – and for good reason. As I think most people

know, our coasts are becoming more populated. There are 153

million people living in our coastal areas in the United

States. Fifty-three percent of our population lives in

coastal areas, and a good number of those Americans live in

hurricane-prone areas.

Now, what we’ve found is that the growth continues in these

areas. If you look at Florida, for instance, from 1950

through the year 2000, there has been a 500 percent growth

in population. Coastal areas continue to be more and more

popular for people to move.

We are right now in what we call a period of more active

hurricane seasons. An active season increases the

possibility of land-falling hurricanes, but before I give

you the numbers, let me be sure that – it just takes one

hurricane to make it a bad year for everyone here. So if

there’s one or 21, we are here today to ensure that the

American public and all those that are concerned with

hurricane management and recovery take into account the

potential for this season and are prepared.

Now, the outlook for this year, as I mentioned, we’re in

above-normal Atlantic hurricane seasonal period. We are

forecasting 13 to 17 named storms, of which seven to 10 will

become hurricanes, and three to five of those hurricanes

will be in the major category, or category 3 strength and

higher.

I want to mention that the ability to be able to do these

forecasts, as well as the forecasts during the season, have

been the results of hours – thousands of hours of work by

our scientists and by scientists in academia, public and

private, to work on an extraordinary partnership in building

the data, the information, the models, and the connectivity

to provide this information.

Everybody should realize that because of the support of the

Administration and Congress, we have within NOAA over $300

million dedicated to hurricane operations and research this

year. And since 2005, we have added $40 million more in

additional resources for hurricane research and operations.

And in this year’s budget, there’s another $10 million

requested in 2008, the budget which is in Congress at this

point. And we want to point out that this investment is well

placed, because it results in an average annual savings to

the country of $3 billion.

One of the special-interest items that we’ve been able to

install in our operations center this year is something

called the HWRF, the Hurricane Weather Research and Forecast

model. We have been working hard on building our – improving

our ability to forecast intensity. This is the latest

state-of-the-art model. It’s a Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere

Model. It is designed to take into account for the first

time airborne Doppler radar data, which will analyze initial

storm intensity and structures. It also makes use of a wide

variety of observations from our satellites, data buoys, and

the aircraft that you see like the one behind me. And there

are two more behind these hangar doors, which I hope that

you will take a look at at the conclusion of this

conference.

But it takes defense in-depth like this to produce the kinds

of forecasts that we’re talking about. And I would like to

just mention that behind me is NOAA’s G4 high-altitude jet.

This was the latest or most recent addition in modernization

to our air fleet. It’s a high-altitude jet that determines

the steering currents and looks at the structure of the

storm and allows us to initialize and look at the steering

currents for the track of the storm.

Now, behind the hangar doors, we have the WP3D, which is the

workhorse of our fleet that goes into the storm and actually

flies through the eye of the storm. It’s a hurricane hunter

designed for research. And right behind that, we have the

C-130J, which actually does the work for tracking hurricanes

during the season. This is managed and run by the U.S. Air

Force. This is the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron,

which does the routine daily tasking throughout the entire

season for us, and is a partner that we could not do

without.

And I want to close by mentioning that without our partners,

we wouldn’t be here today. We see them on the stage here in

terms of FEMA and the Air Force that are represented here

today. We’re delighted to have Secretary Chertoff with us,

David Paulison, the FEMA administrator, Lieutenant General

John Bradley, the head of the United States Air Force

Reserve and very important partner.

Let me close by again saying that this day is about

preparedness. It’s about getting the word out to the

American public that hurricanes are dangerous, they can be

destructive, they can be lethal. It’s our job to give you

warnings in order that you can be prepared. We hope that

everybody will have a safe hurricane season for this year.

Now I’d like to introduce to you Dr. Gerry Bell, our

Seasonal Hurricane Climate Prediction Center Lead Forecaster

who will give you a little bit more on the science behind

the numbers which I just provided.

Dr. Bell.

Dr. Bell: Well, thank you, Admiral. Well, as the Admiral

mentioned, we’re in an active hurricane era that started in

1995. And while we can’t say for sure how long this era will

last, historically other active eras have lasted 25 to 40

years. So we’re now 12 years into an active hurricane era

that could last a total of 25 to 40 years historically.

For 2007, we’re predicting a high probability of an

above-normal Atlantic hurricane season. And just to

reiterate, we’re looking at 13 to 17 named storms, seven to

10 hurricanes, and three to five major hurricanes.

As with other active seasons, active seasons just aren’t

about the numbers, but it’s about where these hurricanes

form. During active seasons, you have a lot of hurricanes

forming in the deep tropics, and it’s called the main

hurricane development region. And many of these storms are

expected to form during August, September and October.

Unfortunately, these are the systems that generally track

westward toward the Caribbean Sea and the United States as

they strengthen, and therefore, they pose an increased

threat to the United States.

Now, although NOAA doesn’t make an official hurricane

landfall forecast, seasons with similar levels of activity

have historically had two to four land-falling U.S.

hurricanes, and, generally, two to three hurricanes in the

region around the Caribbean Sea.

However, it’s important to note that it’s currently not

possible to confidently predict at this time, at these

extended ranges, really, the exact number or intensity of

land-falling hurricanes, or whether a given locality will be

impacted this season.

Because of the extensive research done by the NOAA, the

National Weather Service, and their supporting institutions,

the main climate patterns controlling Atlantic hurricane

activity are now better understood than ever before.

There are two main climate patterns that we expect to be

responsible for the above-normal season this year. The first

is the ongoing conditions that we’ve seen since 1995, and we

call these conditions the multidecadal signal. The second is

the possible development of a La Niña episode in the

tropical Pacific Ocean.

The conditions regarding the multidecadal signal, the

conditions expected this year, again, are very similar to

what we’ve seen since 1995, and that’s when the current

active era began. Since 1995, nine of the last 12 seasons

have been above normal. And of course, we all know the rate

of hurricane landfalls has increased sharply.

NOAA’s extensive research shows that this increased

hurricane activity is related to tropical rainfall, and

Atlantic Ocean temperature patterns that, as I mentioned,

historically tend to last 25 to 40 years at a time.

This multidecadal signal is very important, because it

produces and accounts for the entire set of conditions that

are known to produce active hurricane eras.

The second major predictor for this season is the strong

likelihood of either ENSO-neutral or La Niña conditions

during August to October, which of course is the peak of the

season. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center at this time is

currently indicating La Niña could develop within the next

one to three months. Unfortunately, the combination of La

Niña and an active hurricane era is known to produce very

active hurricane seasons.

Now, even if La Niña doesn’t develop, the conditions

associated with this ongoing active hurricane era still

favor an above-normal season. And as we’ve seen since 1995,

several seasons have been very active, even in the absence

of La Niña.

Looking back for a moment at least year, we over-predicted

the 2006 Atlantic hurricane season, and that was mainly

because of a rapidly developing El Niño during August and

September that subsequently shut the activity down. This

year, we’re not in that situation. Instead, we’re looking at

opposite conditions where we may be transitioning into a La

Niña.

Very importantly, regarding last year, detailed published

analysis by NOAA shows that all of the conditions associated

with the current active era were still in place last year as

we had expected. Therefore, last year’s activity should not

be considered an indicator that this active era has ended.

There is no indication that this active hurricane era has

ended.

This ongoing active hurricane era means that the 2007

hurricane season will again likely be above normal. The

development of La Niña, or really even a La Niña-like

pattern of tropical convection increases the probability for

a very active season and even more hurricane landfalls. Our

predicted ranges of activity reflect this high probability

of an above-normal season.

Now, given that we’re in a bit of a transition debating

ENSO-neutral or La Niña at this time, we’re going to

continue to monitor these evolving climate conditions, and

we’re scheduled to update the outlook in early August.

And now let me introduce Bill Proenza, Director of the

National Hurricane Center.

Mr. Proenza: Good morning, folks. As you’ve heard, NOAA,

with the National Weather Service, is predicting a very

active hurricane season. Your National Weather Service, its

National Hurricane Center, its weather forecast offices

across the country, the river forecast centers are all

ready. Your emergency management community, your local

government officials, they’re ready. With the media, the

emergency management community, we have a terrific

partnership to make sure that we not only keep the American

people aware, but also prepared.

As it stands at this time, we have growing challenges across

this nation, as far as the National Hurricane Warning

program is concerned. Looking at the population growth of

our nation to the vulnerable coasts, we now hear from the

U.S. Census that fully 53 percent of our population resides

within the first 50 miles of the coast. Couple that with the

infrequency that we’ve had over certain sections of the

coastline – for example, in the highly populous eastern

portion of our nation – and, of course, the fact that 2006

was an inactive year, relatively so, we are always concerned

that infrequency can be disarming.

So as the growing challenge is, look at the population that

we have to be effectively warning and effectively getting

out of harm’s way, we’re asking U.S. population in the

coastline areas to join us in what has been a very, very

effective partnership with emergency management, local

government officials, the media, to join us in preparing

yourselves, your families, your businesses, your

communities, to make sure that you have planned to do what

is right to assure the proper response when your area comes

under a hurricane warning, because only together, working

together, can we really make a difference. And we can make

sure that our nation, vulnerable as it is from tropical

storms and hurricanes, can be made to be resilient.

Thank you. With that, I want to introduce one of our

nation’s vital partners. In our National Hurricane Warning

program is the hurricane reconnaissance group of the U.S.

Air Force Reserve Command that’s led by General John

Bradley. The nation so appreciates General Bradley and his

20 crews that fly the Hurricane Hunters out of Keesler Air

Force Base near Biloxi, Mississippi.

General Bradley.

General Bradley: Thank you, Mr. Proenza. It’s a pleasure to

be here. I believe that what we do is a great example of

partnership in government between the Department of Defense,

the United States Air Force, and specifically the Air Force

Reserve Command, and the Department of Homeland Security,

National Weather Service, National Hurricane Center, and

NOAA, as well as FEMA.

So we’re very proud to be a part of this and to help, in

some small way, in preparing our nation for these terrible

storms.

Our 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Keesler Air

Force Base in Mississippi has been doing this mission since

1946. I think the first storm that we flew into was – they

say it was a dare in a bar room that generated the first

flight in 1943 by the Army Air Corps into a hurricane.

That’s not the way we decide to test things anymore, but

it’s interesting that that’s the way it began. But we’ve

been doing this now for a very long time, and I’m very proud

that our airmen of the 53rd Reconnaissance Squadron do this

work for our nation.

We don’t just do these storm-tracking missions during the

hurricane season. We also fly winter storms as well. And

when they’re not doing that, these folks flying the C-130s

fly missions in support of our global war on terror. So

these folks deploy to other places that are very difficult

as well, but I don’t know that the flying there is any more

challenging that hurricane flying.

They fly these storms at about 10,000 feet. They initially

take a cut at this at a much lower altitude, but typically

the missions last 10 to 12 hours. They fly in and out and

fly a triangular pattern, taking different measures of

barometric pressure and other things. They drop a device

called a dropson to measure pressures and winds and so

forth.

This year and next year, we are adding a very nice new piece

of equipment to our aircraft that will help us more

accurately determine the surface winds at all times as the

storm is out over the water.

So we hope that the little bit that we do in flying through

these storms gives us a better predictor. They say maybe

it’s a 25 to 30 percent more accurate reading of the

intensity of the storm and where it might hit because of

flying through these storms.

I’m proud of these folks that do this. I hope you’ll take

the opportunity after this conference to go meet our crew

and see the airplanes, see the equipment that we use as we

try to tell the American people what we do to prepare our

nation for these storms.

Again, the Air Force Reserve Command and our Air Force is

very proud to be in this partnership, to help our nation

prepare for these what can be disastrous consequences. And

now as we transition into the preparedness, we are honored

to have the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security

with us, as well as the Director of FEMA. So our next

speaker I’m proud to introduce is Secretary Michael Chertoff.

Secretary Chertoff: Thank you, General, for the

introduction, and thank you, everybody else, for your

comments.

I’m going to be very brief. I just want to make three

points. Whatever hurricane season may bring, we obviously

hope for the best but we prepare for the worst. And I think

that means three things. First of all, speaking for the

Department of Homeland Security, represented also here by

Administrator Dave Paulison of FEMA and by the Coast Guard,

which is represented by the helicopter, all of us have

worked very hard over the last year with state and local

government, who are the first responders, to carefully

review emergency planning and evacuation planning so that

everybody is prepared for this year’s hurricane season.

And it’s important to emphasize that although we typically

think of hurricanes as hitting the Gulf area or the area of

Florida and the Carolinas, it is quite possible to have a

hurricane further north in areas which are less accustomed

to dealing with hurricanes. And it’s been important to

emphasize to state and local officials there that they also

have to make sure that their emergency and evacuation plans

are dusted off and exercised.

Second, we are coming into this hurricane season with a set

of tools that we’ve never had before. We’ve got much more

communications equipment, including interoperable equipment

that is capable of being put on-site very quickly, including

real-time video to give us eyes on the actual situation when

the storm hits.

FEMA has worked very hard to get increased visibility into

the movement of goods and supplies as we move forward, to

see how we respond to a hurricane if it hits, and then we’ve

built a series of business processes and tools which will

enable us to enroll people if they’re suffering upheaval

because of the hurricane, will let us get assistance to them

more promptly, will guard more securely against the

possibility of fraud and abuse. And Administrator Paulison

will talk about these a little bit more when he comes up

here.

There’s one third and most important piece of the puzzle,

and that is individual preparedness. The fact is that no

matter how good your local responders are, your state

responders or your federal responders, they will not be

there instantly at the time a hurricane arrives.

It is the preparation of individuals, families and

businesses that makes the difference between survival and

disaster when a hurricane hits. That means preparing

yourself with the necessary tools, preparing yourself with

food and water to sustain you for up to 72 hours, having a

plan about what you do, and, most important, listening to

the guidance of your local officials about when to get out

in advance of a storm. A storm is no place to be a hero. And

the fact that somebody rides out a storm and puts themselves

in peril is not only an endangerment of their own lives, but

actually endangers the responders who have to get in there

and do the rescues.

So my view is, it’s kind of a civic responsibility for

everybody who’s in the zone of danger to take the steps

necessary and to listen to the instructions given so that we

can allow our responders to attend to those people who can’t

help themselves.

Finally, let me echo something that Bill Proenza said – and

I’m going to be as blunt as possible: Last year was an

unexpectedly easy season; there’s no guarantee that this

season is going to be anything less than very tough.

Complacency and disarming yourself are the biggest threats

that people face, in terms of getting themselves prepared.

It is a big mistake to count on being lucky. You’re much

better off preparing yourself for the worst, and then if you

get lucky, that’s a bonus.

So I think we’re all going to be up there urging that

message of fight complacency and be serious about this

before the hurricane season actually starts to hit in June.

I’m going to now introduce Dave Paulison, our Administrator

of FEMA, who has been at my side for the last couple of

years dealing with hurricanes and who brings a lot of

personal experience, going back to his days being fire chief

in Dade County to this hurricane challenge.

Dave.

Administrator Paulison: Thank you, Mr. Secretary. I think

this is like a congressional hearing. Everything that needs

to be said has been said, just everybody hasn’t said it yet.

But I do want to talk about a couple of things. One, we have

been working very hard, very closely with the Secretary to

make sure that the federal government is going to be ready –

not just FEMA, but the entire federal family – developing

those partnerships, putting those pre-scripted mission

assignments in place, putting contracts in place, working

with the states along the Gulf Coast, up the Atlantic Coast,

with Puerto Rice and the Virgin Islands, to do those gap

analyses to see where the issues are, where those gaps that

we can help them fill so we can tailor our response.

But what really keeps me awake at night, what really keeps

me awake at night, is something the Secretary touched on,

and that’s about personal preparedness. I spent this last

weekend, after I flew down to Florida Friday night, to start

getting my home ready – making sure my shutters worked,

opening and closing all of them, making sure my generator

ran, and making sure we have the things that we need to get

through hurricane season.

If we are going to survive these storms, if we’re going to

get into the recovery process much more smoothly that we

have in the past, it takes all of us to be ready. It takes

the federal government to be ready, and that’s our

responsibility to make sure that happens; the state

governments have to be ready; the local governments have to

be ready to respond. But so does the local community, the

local citizens have to be ready to respond and prepare

themselves for these storms – making sure they have a plan,

like you heard the Secretary say, about an evacuation. If

you’re in an evacuation zone, if you’re going to ride out a

storm, make sure you have your three-day supply of food,

water, flashlight, batteries, medicines, taken care of your

pets, making sure you have supplies for your children, all

of those types of things you’re going to have to survive for

the three or four days before help can truly arrive. That, I

think, is the most important thing.

If we all do our part, if all of us –the federal government,

the state and local community, and us as individuals – we

can’t stop the storm from coming, and we can’t necessarily

stop the damage, but we can also – together, we can get

through this and survive much, much better than we have in

the past.

So that’s my concern. My concern is the complacency that

we’ve seen in the past, the complacency we saw, quite

frankly, year before last with Hurricane Wilma in my

hometown of Florida, where we had tens of thousands of

people lined up for food and water and ice when they should

have been able to take care of themselves. We cannot

tolerate that anymore.

So I would ask emergency managers out there listening, the

media around in this room, that’s the message we have to get

across. We have predicted a very heavy hurricane season. We

need to make sure that those who are in those hurricane

zones have prepared themselves for this upcoming season.

And thank you very much. We can take a few questions now.

Mr. Franklin: Thank you, Director Paulison. When I recognize

you, we have time for just a few questions. Please state

your name and affiliation and to whom you’re addressing your

question. Yes, sir.

Question: A question for Secretary Chertoff. Hurricanes Rita

and Katrina in ‘05 took out 100 percent of Gulf Coast oil

production, 90 percent of gas production, and shut down,

what was it, seven refineries in the Gulf Coast region. Are

you assured by those various industries that they have – are

better able to survive a hurricane strike of that magnitude

now than they were then?

Secretary Chertoff: Well, the first thing is, of course,

there’s only so much you can do to resist a hurricane. I

know that the various companies involved have learned

lessons in taking steps based upon the experiences they had

in the Gulf storms of 2005 to build greater resiliency. But

I also want to be up front in recognizing that wind and

water can do an awful lot of damage, and nobody is

invulnerable to them.

One issue we have asked, we asked last year and we’re asking

again this year for all of the energy companies is to make

sure that their individual gas stations and their franchises

have generators available. One of the big lessons we learned

in 2005 is, if you don’t have generators to get the pumps

working, people can’t get to work, they can’t get food, they

can’t get water. Energy is the cornerstone of recovery and

resilience.

And so, as we did last year, we’re going to ask them to make

sure those generators are down there ready to go, both to

help people get the gas they need to evacuate, but also to

help get started up again after a storm.

Question: Thank you. This is for Secretary Chertoff. What

have you learned since your personal failure in your

response to Hurricane Katrina?

Secretary Chertoff: One thing I’ve learned is that some

reporters ask loaded questions. I’ll tell you what I’ve

learned. I’ve learned that the key to any successful

response is preparedness. No matter how good somebody is, if

you walk into an emergency, you’re not going to be able to

improvise a solution. That means the planning to deal with

issues has to begin years in advance. And one of the things

we’ve all learned from 2005 is how to do that planning.

That’s why we have the capabilities and the tools this year

that we didn’t have in 2005, and that’s why we have plans

with the Department of Defense this year that we didn’t have

in 2005, and frankly, that we didn’t have in the 1990s or

1980s either. And that’s why we’ve been working with state

and local authorities to make sure they’ve done their

planning properly because, again, the first responders have

traditionally been and will always be state and local

authorities. They’re the ones who know the people, they know

the landscape, they’re going to be close to the storm, and

therefore they have to get their plans in order and

synchronize with ours in order to be able to react properly.

So you’ve got the benefit this year of two years of

investment of substantial resources, an administrator of

FEMA who has real expertise, a great partnership with the

Department of Defense and the Department of Commerce, and a

lot of planning with state and local authorities, many of

whom I’ve spoken to personally and looked in the eye to make

sure that they have fully stepped to what they need to do.

Question: This is a question first for the Admiral, and then

for Mr. Proenza. Admiral, a report by NOAA recently came out

and said that seven years after the first operational use of

ocean surface vector winds, the nation – that means NOAA –

still doesn’t have a plan to operationally measure these

winds after the QuikSCAT satellite is gone. What have you

been doing for seven years? You’ve been there for five. Then

the other question for Mr. Proenza is, what does this lack

of data, if we were to lose QuikSCAT, mean for your

forecasters?

Admiral Lautenbacher: There has been a plan, and the plan

has been in place for a long time. We have two experimental

satellites. One is QuikSCAT, and one is the Coriolis

WindSat, which was launched not that long ago and will last

longer than the scatterometer.

We have been learning, in the last couple of years, to use

vector windfield data in our models, and it’s proven to be

very important. Our original plan was to use the conical

microwave imaging scanner to provide the vector windfield

data. We are relooking at that, based on the recommendations

of Mr. Proenza at this point, and I’ve asked my team to go

back and review it again, along with our satellite experts,

to see what would be practical, in terms of providing for

continuity of scatterometry data versus switching to the

Conical Microwave Imaging Sounder. So that’s the situation

we have at this point. Thank you.

Mr. Proenza: The satellite known as QuikSCAT provides us

operationally and has been used operationally since 2000,

especially for our hurricane program. As it stands, it is a

broad swath of data that comes across to us, that shows the

envelope in which a storm may be existing; that indicates to

us not only wind speed, but also wind direction. It gives us

an estimate of the size of the tropical storm winds and the

hurricane winds. It’s a vital piece of data to us in our

operational National Hurricane Warning program, as it is for

the high seas forecasting for not only the nation, but it is

a service that’s used over 90 percent of the global oceans.

We have had several discussions along the lines of how we

can increase the priority for a QuikSCAT replacement. I am

encouraged in those conversations that we have had, and

discussions we have had, that the nation will be moving

ahead very constructively in coming up with a design

next-generation QuikSCAT to replace the current, which is

still operational QuikSCAT that we have at this time.

Question: With another active hurricane season – this is for

Mr. Paulison or Mr. Chertoff – some governors are, I’m sure,

going to express their concerns again that there may not be

enough National Guardsmen at home to take care of it. Is

this a concern for NOAA – for FEMA or the Department of

Homeland Security? And also, what are the numbers – what are

the numbers of Guardsmen who are going to be here and

available this year, as opposed to 2005 and 2004, the other

active hurricane seasons?

Administrator Paulison: It’s an issue we’ve talked about

quite a while with the adjunct generals – when I was in

Kansas, visiting there with the adjunct general, making

comments about how he was at 50 percent of his authorized

force strength. But 50 percent is a wartime strength issue,

and the fact that the equipment that he had on the ground

for responding to natural disasters was significant. But I

also told him how we respond in this country, using what we

call the Emergency Management Assistance Compact system,

where we bring in not only National Guard, but resources

from all the other states – all 50 states in this country

are part of that system, where we share resources with one

state to another.

If one state has a disaster or some type of catastrophe it

has to deal with, it puts out through this EMAC system the

equipment that it needs, and then it starts flowing from the

other states. During Hurricane Katrina, we actually had

National Guards from all 50 states into that state to help

them out with those disasters. On top of that, we can bring

the Army Corps of Engineers in – it has heavy equipment. We

have contracts in place already to bring those types of

equipment in. So I’m very comfortable that regardless of

what happens, particularly a hurricane, we can flow

equipment and supplies and staffing into a particular state

to cover those areas.

Question: (Inaudible.)

Administrator Paulison: I couldn’t answer that. I can tell

you, my own home state of Florida, Craig Fugate announced –

said at the hurricane conference that he has more people

available to him this year than he had in the past. That’s

the only state that I’m aware of.

Question: A question for Admiral Lautenbacher. Admiral, sir,